Risk & Resilience in Logistics Network Design

Reimagine resilience and proactively minimize supply chain risks

If it is about identifying trends at an early stage or about taking timely countermeasures in the event of problems in the supply chain – we reach better decisions when they are based on data that is as accurate and up to date as possible. To optimize business processes, it is worth using process mining in addition to data mining or machine learning on the data itself: process mining analyzes the event logs of operational systems for data traces that business processes leave behind. This article highlights the potential of process mining using concrete case studies from chemical and pharmaceutical logistics.

Process mining illustrates the different process variants and their frequencies. This allows deviations from the TARGET to be determined and process variants to be identified. The visual processing of the results identifies process diversity, process breaks, inefficiencies and their causes. Pharmaceutical and chemical logistics are well prepared for using the technology: the logistics processes are generally already IT-based, both in the transport and warehouse environment as well as in plant logistics. Combining and analyzing the process-related data from the event logs of the systems reveals important insights that can lead to increased transparency or reduced lead times. Furthermore, process mining provides a realistic overview of the actual processes and their variants in logistics for the first time in many cases – this feature already goes a long way towards better decisions.

A further driver for process mining in chemical and pharmaceutical logistics are positive effects on turnover and competitiveness: increases in process efficiency bring substantial savings potential for the often high cost of logistics. In addition, logistics performance contributes significantly to customer satisfaction.

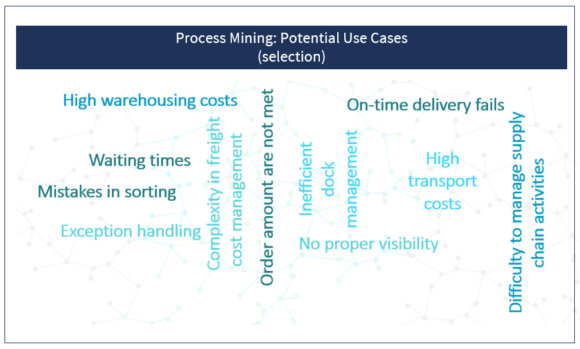

Process mining can provide answers to complex questions in pharmaceutical logistics, such as “on time in full” performance in distribution to pharmacies, hospitals and wholesalers. Here, data and systems from external partners would have to be included in the analysis, making this a rather complex use case. Initially, we recommend leveraging the potential from analyses of internal processes, i.e. from order entry to shipping. Here it is possible to rapidly optimize actual process run times as well as variants. The multitude of process variants and the variance of process run times alone often provide surprises. Three additional examples are presented below in more detail. Figure 1 gives an overview of possible applications.

The use cases for process mining provide an important indication when deciding whether process mining knowledge should be built in-house or brought in selectively from external sources. The underlying question is one of frequency of use, one-time use versus continuous use.

A one-time use takes a snapshot in time, for example to assess the current process variants. In this case, it is often sufficient to cooperate selectively with an expert who, in addition to specific industry and process mining experience, brings the appropriate software licenses for the project. Specific potential for improvement can be derived from the results of the analysis that are then structured in a roadmap. One cost-efficient option to check the success of the measures is to repeat the assessment at regular intervals by means of a review.

If, on the other hand, a set up for continuous KPI reporting and thus continuous process monitoring is the goal, it pays off to build in-house knowledge and invest in process mining software licenses.

No matter which alternative you opt for, the results of process mining can be very comprehensive. They usually pertain six core dimensions (see Fig. 2). In the following, we share use case examples where process mining quickly led to success.

In warehouse operations, the “Dock 2 Stock” KPI indicates the time it takes to receive goods, and thus make them available for ordering and shipping. It is not uncommon for the exact definition of the KPI to be misleading. It can be analyzed more precisely with the aid of process mining by collecting time stamps and document flows from the event logs of the systems for yard and inventory management. Collecting the time stamps starts with the arrival of the truck, goes through unloading and quality control, and includes the release of the stock. For this, the event logs of the inventory management system are used. Depending on the depth of analysis, there are different insights that can be gained, as, for example, for transit times or quality control processes. Even in the regulated pharmaceutical environment, segmentation often allows for a much faster batch release.

With process mining, you can collect differentiated information about the dwell time of requested goods in the provisioning area. To do so, time stamps from incoming orders can be combined and analyzed. They are often available as they are generated by production planning as part of production supply. This analysis can reveal weaknesses in the planning, reliability or transparency of production supply. In addition, it can potentially streamline processes, reduce process costs and inventories and optimize the use of available buffer space.

Penalties or additional charges are generally incurred for load carriers used in chemical logistics for sea freight, inland shipping or rail transport after the contractually agreed period of use has expired. The supplier’s claims can only be assessed if the way-of-use of a load carrier is recorded from receipt to return. Potential savings become apparent if one focuses on the steps between the release of a load carrier and its return.

In many cases, it is possible to optimize where and when the load carrier is returned on schedule, or in which cases a longer period of use should be agreed – at more favorable conditions – right at the outset. The data helps to improve the utilization of the agreed payment target and thus the cash flow. As a rule, costs can be reduced considerably without impacting operational processes. However, this example poses some implementation challenges: process mining tools do not initially identify stock levels because stocks do not have transaction documents. In addition, the material ID can change during the production process. This may require some experience to link the warehousing ID and retrieval ID.

Process mining has enormous value-creation potential, even for the pharmaceutical and chemical industry. Logistics is an ideal environment, as the conditions here are already good – keyword: high level of process digitalization. After initial tests, it is worth analyzing the potential of process mining in your own company. Is it more about selective snapshots that are implemented with external partners? Or is there potential for constant improvements accompanying the processes? In both cases, the technology is mature enough to leverage genuine potential for optimization with user-friendly applications.

We would like to thank Thomas Schnur for his valuable contribution to this article.

Reimagine resilience and proactively minimize supply chain risks

This article shall help you to understand how to optimize your inventory positions in a month – or even less.

Modern PLM systems empower businesses to achieve product excellence in fast-paced markets by enhancing collaboration, agility and innovation.

Read how the Campaign Planner & Designer (CPD) helps you to manage supply chain variability.

© Camelot Management Consultants, Part of Accenture

Camelot Management Consultants is the brand name through which the member firms Camelot Management Consultants GmbH, Camelot ITLab GmbH and their local subsidiaries operate and deliver their services.